From Ennio Morricone and Piero Piccioni to Bach and Vivaldi, soundtracks are a tool to better decipher the equally sacred and profane approach of the author and director to cinema and the meanings assigned to his films.

When in 1971 Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange was released more than one viewer was probably perplexed by the association of the futuristic interiors and settings with the ancient music of Ludwig Van Beethoven. The classical composer, though, was much more than a mere background to the Droogs’ adventures and ultraviolence, but was elevated to a higher symbolic relevance by the director.

Ten years earlier, though, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s cinematic debut Accattone had already explored similar scenarios, when juxtaposing the music of J.S. Bach to scenes of teenage working-class deviation. Like noted by author Donald Greig in his article ‘Somewhat of an affectation: Bach, Vivaldi and the early films of Pier Paolo Pasolini’, published in the February 2022 issue of Music and Letters, the audience encounters the “strangeness of the musical choice and in particular its sociocultural disconnection from the film’s setting of the borgate, the deprived areas on the outskirts of Rome”.

And this applies to his follow-up oeuvre too, Mamma Roma (1962) the soundtrack of which, next to the two original compositions by Carlo Rustichelli on CAM Sugar, features the music of Antonio Vivaldi.

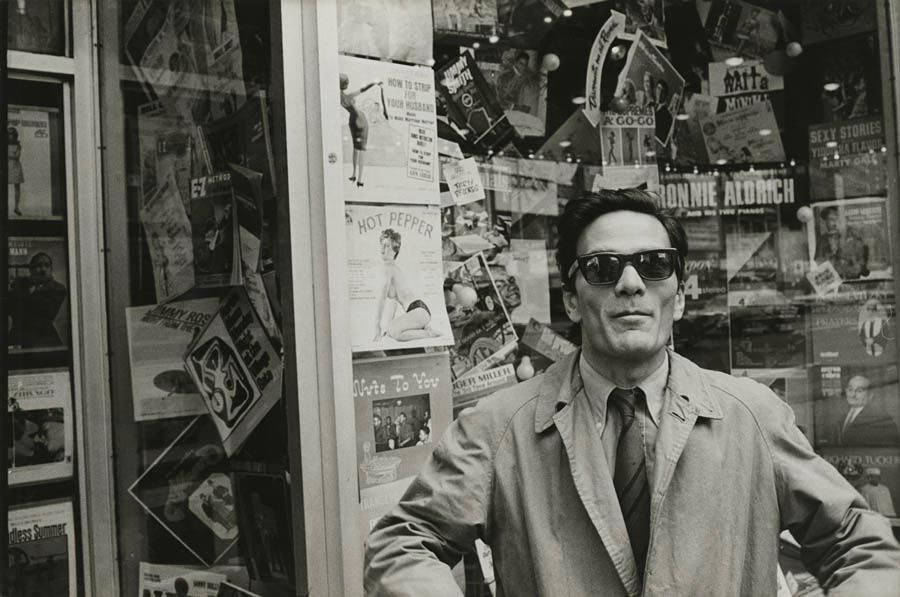

The deep spirituality of the author, next to his attraction for the controversies of consumerist culture in post-war Italy, resulted in more or less explicitly dotting his films with religious references. It is Greig, again, to note how the stories of the main characters of Accattone and Mamma Roma echo the life of Christ, from the Marian-like figures of Maddalena and Stella in the first, to the death of Ettore staged according to Andrea Mategna’s painting Lamentation of Christ in the latter, to mention just a few. Similarly, The Deposition from the Cross (or Volterra Deposition, 1521) by Rosso Fiorentino would serve as a reference for the crucifixion staged in ‘La ricotta’, his episode in the omnibus film Ro.Go.Pa.G. (1963). Yet, Pasolini was also the intellectual hanging with the Roman jet-set, and dripping in sartorial savoir-faire, including the famous colour portrait with a Gucci belt.

Just like in his films the Christian Catholic iconography unfolds next to trivial and mundane scenes of everyday life, the same takes place in the soundtracks that came to define the cinema of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Next to the baroque, classical and religious music of the likes of Joahn Sebastain Bach, Antonio Vivaldi and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, stood the interventions of the cream of Italian soundtrack composers: Carlo Rustichelli, Luis Bacalov, Giovanni Fusco, Piero Piccioni and, of course, Ennio Morricone. Their scores represent much more than mere background music, but offer surgical social commentary to the stories and dynamics explored by the director.

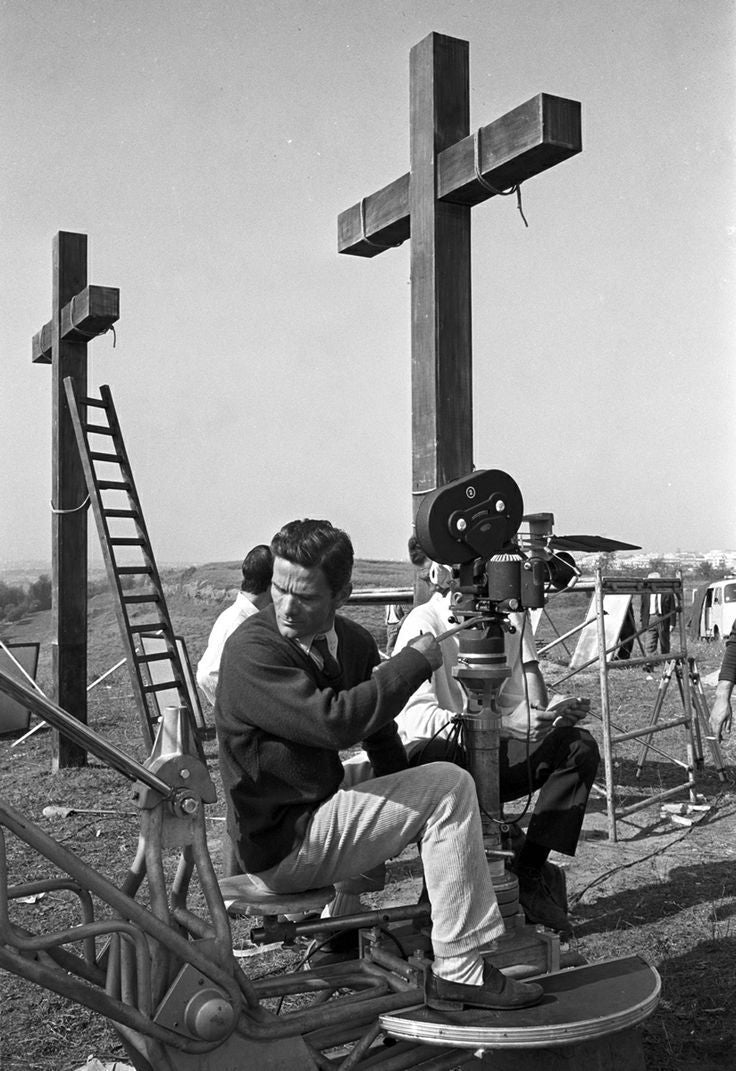

Pier Paolo Pasolini on the set of 'La ricotta', Ro.Go.Pa.G., 1963.

Many of the soundtracks of his early films had remained unpublished in their entirety for decades, until CAM Sugar rediscovered them in its vast archive and brought them back to life, fully remastered, in 2022 on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the birth of the Casarsa author, director and intellectual. You can listen to them as part of the digital collection 100 Years of Pasolini: The Early Days.

We have selected 5 scores that offer an insight into the musical identity of Pasolini’s cinema.

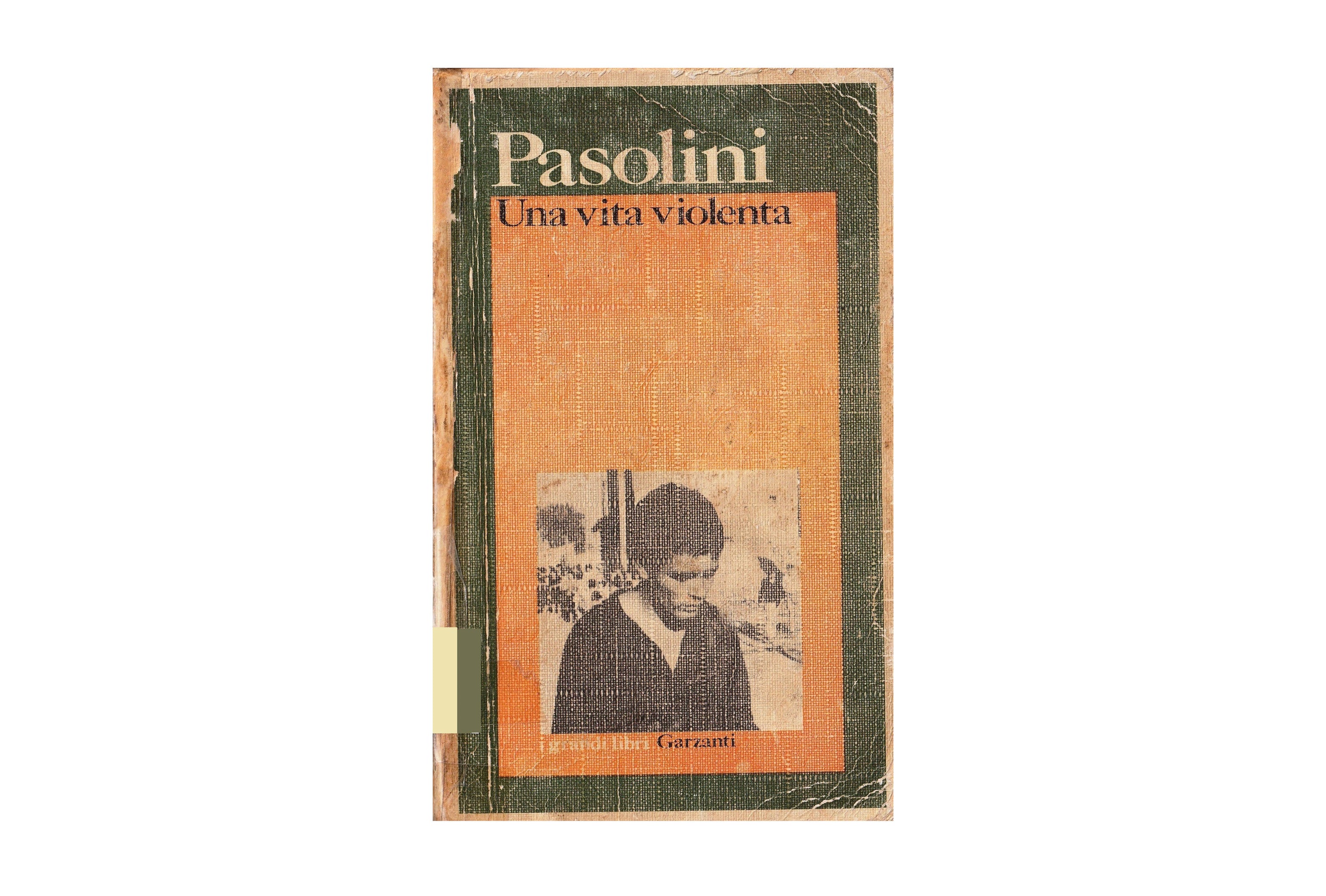

Piero Piccioni – Una vita violenta (1962)

Una vita violenta was first published as a novel in 1959.

Una vita violenta was first published as a novel in 1959.

always the novels by Pasolini ended up on the big screen directed by their author. It is the case, for example, of Una vita violenta. Published in 1959 for Garzanti, the book was one of the finalists of that year’s Premio Strega, where another novel set to make cinema history would win: Il gattopardo by Filippo Tomasi di Lampedusa.

Three years later Pasolini’s story was turned into a film, directed by Paolo Heusch and Brunello Rondi. It starred Enrico Maria Salerno, Serena Vergano and Franco Citti, the Roman youngster discovered the previous year by Pasolini himself, who had assigned him the role of main character in Accattone.

The soundtrack by Piero Piccioni on CAM Sugar captures all the teenage drama and alienation of early 1960s working-class life in Rome while retaining the typical cool and hip identity of the modern jazz of the time. The result is one of the best scores by the modern gentleman of Italian film music, equally tense, swinging and sophisticated especially in cuts like ‘Tu sarai così’, 'Jazz Theme Song' and ‘Autoradio’.

Carlo Rustichelli, Giovanni Fusco – Ro.Go.Pa.G. (1963)

Pier Paolo Pasolini on the set of La Ricotta, taken from Ro.Go.Pa.G., 1963.

This omnibus film saw the participation of some of the most acclaimed directors, actors and intellectuals of the time, both behind and in front of the camera. Roberto Rossellini, Jean-Luc Godard, Pier Paolo Pasolini and Ugo Gregoretti each direct an episode, giving the enigmatic name to the film.

Starring Orson Welles, Pasolini’s ‘La ricotta’ was accused of blasphemy for his harsh and caustic reflection on the value of spirituality in the consumerist culture of the 1960s.

Carlo Rustichelli’s cha cha cha and twists highlight the striking contrast between the frenzy of post-war life and the scene of the deposition of Jesus Christ, which an American director (Welles) is trying to film while pestered by the roman press.

The complete score has been made available for the first ever in its entirety and fully remastered by CAM Sugar, and also includes Giovanni Fusco’s ‘Eclisse Twist’, originally included in the soundtrack for Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’eclisse.

Ennio Morricone – Uccellacci e uccellini (1966)

Totò and Ninetto Davoli, Uccellacci e uccellini, 1966.

The Maestro’s creative bond with Pasolini began on Uccellacci e uccellini, one of the director’s most acclaimed works. As the author became more and more interested in exploring the expressive potential of music in his films, Morricone was able to capture the weight of spirituality and to fuse it with the epic charge mastered with his Spaghetti Western scores.

The film’s sacred and profane stance finds a striking correspondence in the soundtrack by Morricone. The opening and end titles featuring vocals by Domenico Modugno represent one of the quirkiest peaks of creativity in film music history. The exquisite example of meta-soundtrack sees a narrator (Modugno) introducing and wrapping the story and its characters up in the style of Mediaeval novels, while commenting with cheek on the risks Pasolini and his producer Alfredo Bini faced by making the film.

The vocal opening titles are part of CAM Sugar’s Morricone Segreto Songbook collection, available on 2LP, CD and digital.

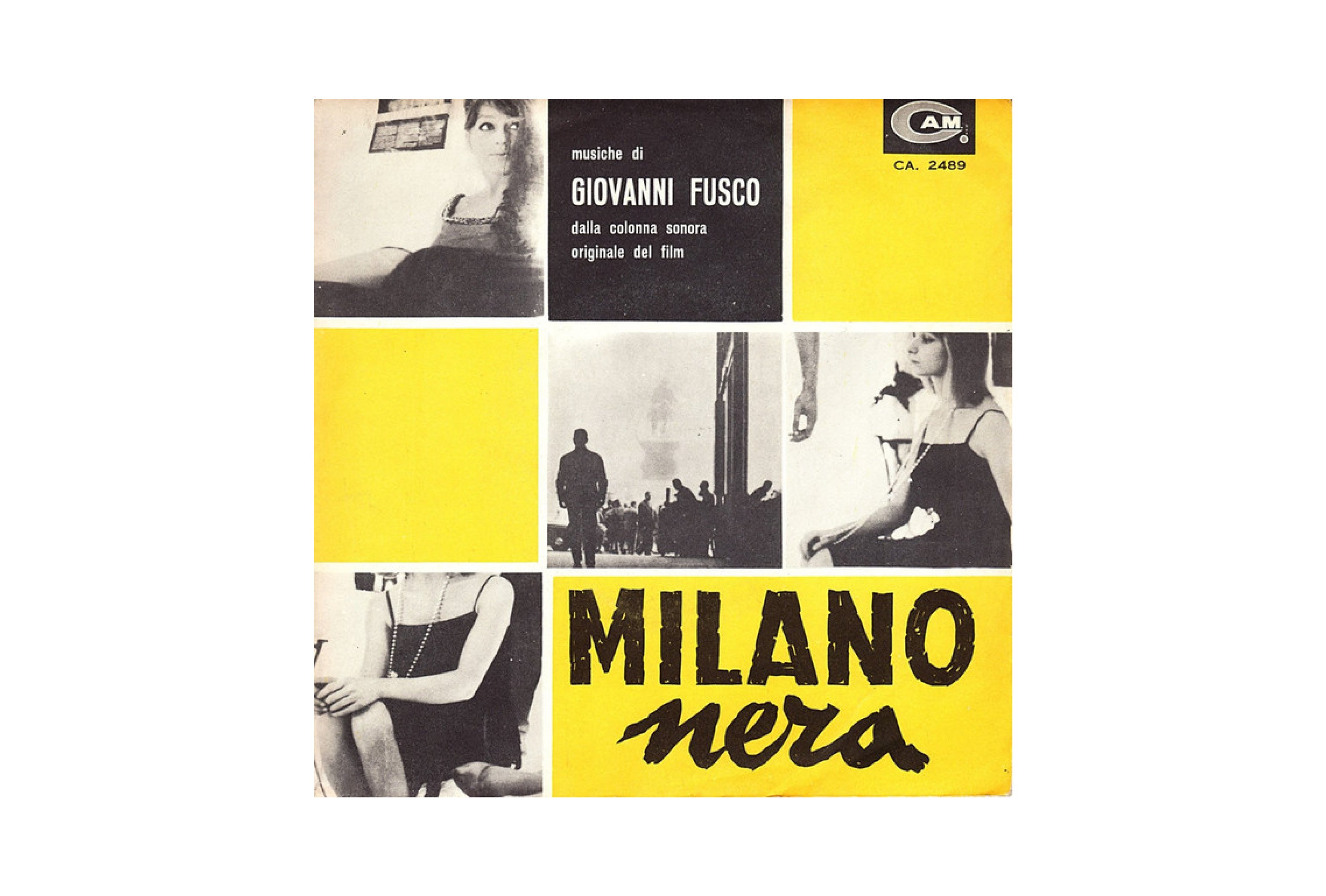

Giovanni Fusco – Milano nera (1961)

The original CAM 45rpm for Milano nera, music by Giovanni Fusco.

Before the advent of Ennio Morricone as the ultimate composer of intellectual cinema in the mid-to-late 1960s, Giovanni Fusco had been offering his unique blend of hermetic, alienating themes and popular music to the service of engaged directors like Antonioni.

Milano nera is one of his best achievements, although highly overlooked. The score was brought back to light from the CAM Sugar archive in its entirety for the first time in 2022, when for years only the film’s vocal theme had been known via its 45rpm release.

Milano nera is another example of a film which Pasolini didn’t direct, although his signature is all over it. The intellectual had been commissioned an investigation on the underworld of Milanese youth deviance, which would represent Pasolini’s first work outside his comfort zone of Rome. Originally scripted with the title of La nebbiosa, the foggy [city], the opus, though, was abandoned by PPP with directing duties ending up in the hands of Pino Serpi and Gian Rocco.

The film suffered from bad distribution and soon slipped into oblivion, only to miraculously resurface in the 2000s when a copy was rescued from a cinema gone out of business. The soundtrack is an equally surprising finding, with Fusco amalgamating the Teddy Boys’ love for twist and rock’n’roll with modern jazz, intended as a sonic commentary to the rising and expanding face of Milan, a city caught in an alienating whirlwind of neon lights, rising steel and glass skyscrapers, consumerism and youth violence.

Ennio Morricone – Teorema (1968)

Teorema, archive photo from the set, 1968.

Despite Pasolini abruptly interrupting his work on La nebbiosa/Milano nera, a few years later he would return to Milan, this time to direct his definitive milanese opus: Teorema. The allegorical bourgeois drama, exploring art, spirituality and homosexuality starring, among others, Terence Stamp, Silvana Mangano and Laura Betti, marked another opportunity for Pasolini to collaborate with Ennio Morricone.

The mini-soundtrack is one of Pasolini’s most psychedelic and pop moments, which no doubt resents the glamorous, late-1960s environment the film was set in. For this score Morricone served himself with the aid of Trio Junior, a teenage beat three-piece from Milan, who performed the vocal track ‘Fruscio di Foglie Verdi’, also part of CAM Sugar Morricone Segreto Songbook.

Opening image: Pier Paolo Pasolini in New York, 1966.